Posts Tagged ‘performance feedback examples’

The people you work with want to do a good job. They want you to think well of them. Yes, even the people you think do little work. Give people the benefit of the doubt. Assume people are doing the best they know how to do. And when you don’t get what you want, make requests.

There are two ways to give feedback. One way is very direct.

Version one: “You did this thing and here’s why it’s a problem.”

The other way is less direct. Rather than telling the person what went wrong, simply make a request.

Version two: “Will you…” Or, “It would be helpful to get this report on Mondays instead of Wednesday. Are you able to do that?”

It’s very difficult to give feedback directly without the other person feeling judged. Making a request is much more neutral than giving direct feedback, doesn’t evoke as much defensiveness, and achieves the same result. You still get what you want.

When I teach giving feedback, I often give the example of asking a waitstaff in a restaurant for ketchup. Let’s say your waiter comes to your table to ask how your food is and your table doesn’t have any ketchup.

Option one: Give direct feedback. “Our table doesn’t have any ketchup.”

Option two: Make a request. “Can we get some ketchup?”

Both methods achieve the desired result. Option one overtly tells the waiter, “You’re not doing your job.” Option two still tells the waiter he isn’t doing his job, but the method is more subtle and thus is less likely to put him on the defensive.

You are always dealing with people’s egos. And when egos get bruised, defenses rise. When defenses rise, it’s hard to have a productive conversation. People stop listening and start defending themselves. Defending oneself is a normal and natural reaction to negative feedback. It’s a survival instinct.

You’re more likely to get what you want from others when they don’t feel attacked and don’t feel the need to defend themselves. Consider simply asking for what you want rather than telling people what they’re doing wrong, and see what happens.

I will admit, asking for what you want in a neutral and non-judgmental way when you’re frustrated is very hard to do. The antidote is to anticipate your needs and ask for what you want at the onset of anything new. And when things go awry, wait until you’re not upset to make a request. If you are critical, apologize and promise to do better next time. It’s all trial and error.

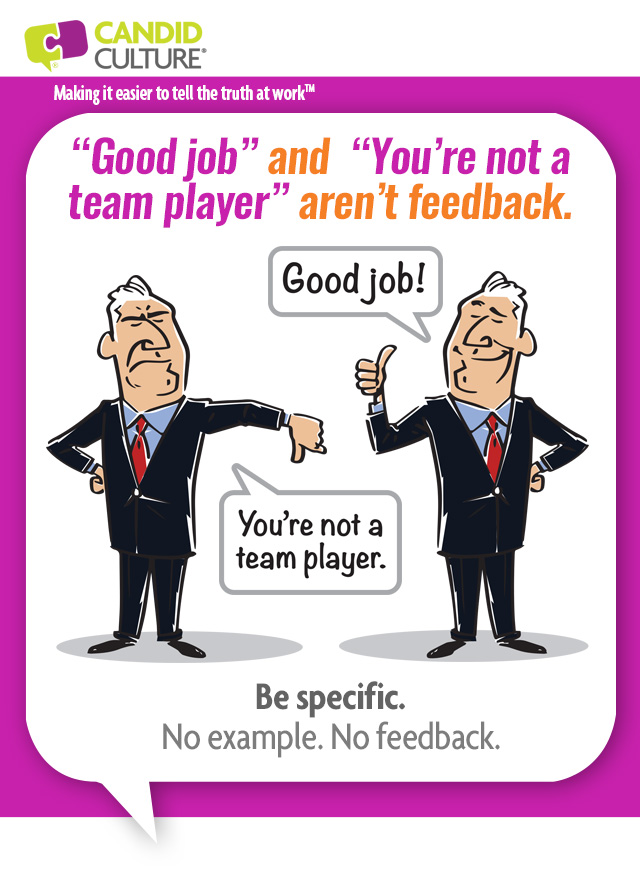

Want to know why people get defensive when you give feedback and why they often don’t change their behavior? Because what you’re giving them isn’t actually feedback.

“You’re awesome to work with” isn’t feedback. Neither is “You did a great job.” “Your work isn’t thorough” isn’t either. Neither is, “You were inappropriate.”

Most of what we consider feedback isn’t feedback at all. It’s vague, unhelpful language that leaves people wondering what they need to do more, better, or differently.

There are only two reasons to give feedback – to encourage someone to either change or replicate a behavior. Unfortunately, most of the ‘information’ we give is too vague to help people do either.

When you give coach or give feedback, you serve as someone’s GPS. Like the GPS on your phone, you need to be so specific the person knows precisely what to change or replicate. If you were driving and your GPS said, “Good job” or “I think you’re off track,” you’d throw the GPS out the window and get a map.

If you give someone what you consider feedback and he says, “I don’t know what you mean, can I have an example?” you’ll know you weren’t helpful.

Here are six tips for giving helpful feedback:

Giving feedback tip one: Write down what you plan to say, then strip out half the words. Shorter feedback with fewer words is better.

Giving feedback tip two: Practice what you plan to say out loud. Have you noticed that what you ‘practice’ in your head is typically not what comes out of your mouth?

Giving feedback tip three: Before having the ‘real’ conversations, give the feedback to an independent, third party and ask her to tell you what she heard. Ensure who you talk with will maintain confidentiality. Your organization doesn’t need more gossip.

Giving feedback tip four: Tell someone else about the conversation you need to have, and ask him what he would say. Anyone not emotionally involved in the situation will do a better job than you will. Again, ensure confidentiality.

Giving feedback tip five: Ask the feedback recipient what he heard you say. Asking, “Does that make sense?” is an ineffective question. “Do you have any questions?” isn’t any better.

Giving feedback tip six: Give one to three examples of what the person did or didn’t do, during the conversation. If you don’t have an example, you’re not ready to provide feedback, and anything you say will evoke defensiveness rather than behavior change.

Giving feedback doesn’t have to be so hard. Be so specific that your feedback could be used as driving directions. The purpose of feedback is to be helpful.

I’ll never forget a coaching meeting I had about two years ago. I gave the manager I was coaching some tough feedback and he replied by saying, “I know I do that.” So I asked him, “If you know this is an issue, why are we having the discussion? He told me, “I just figured this is the way I am.” And I realized that knowing a behavior is ineffective doesn’t mean we know what to do to make things better.

I’ll never forget a coaching meeting I had about two years ago. I gave the manager I was coaching some tough feedback and he replied by saying, “I know I do that.” So I asked him, “If you know this is an issue, why are we having the discussion? He told me, “I just figured this is the way I am.” And I realized that knowing a behavior is ineffective doesn’t mean we know what to do to make things better.

The people you work with want to do a good job. They want you to think well of them. Yes, even the people you think do little work and/or are out to get you. Give people the benefit of the doubt. Assume people are doing the best they know how to do. And when you don’t get what you want, make requests.

There are two ways to give feedback. One way is very direct.

Version one: “You did this thing and here’s why it’s a problem.”

The other way is less direct. Rather than telling the person what went wrong, simply make a request.

Version two: “Would you be willing to…” Or, “It would be really great to get this report on Monday’s instead of Wednesday. Would you be willing to do that?”

It’s very difficult to give feedback directly without the other person feeling judged. Making a request is much more neutral than giving direct feedback, doesn’t evoke as much defensiveness, and achieves the same result. You still get what you want.

When I teach giving feedback, I often give the example of asking a waitstaff in a restaurant for ketchup. Let’s say your waiter comes to your table to ask how your food is and your table doesn’t have any ketchup.

Option one: Give direct feedback. “Our table doesn’t have any ketchup.”

Option two: Make a request. “Can we get some ketchup?”

Both methods achieve the desired result. Option one overtly tells the waiter, “You’re not doing your job.” Option two still tells the waiter he isn’t doing his job, but the method is more subtle and thus is less likely to put him on the defensive.

You are always dealing with people’s egos. And when egos get bruised, defenses rise. When defenses rise, it’s hard to have a good conversation. People stop listening and start defending themselves. Defending oneself is a normal and natural reaction to negative feedback. It’s a survival instinct.

You’re more likely to get what you want from others when they don’t feel attacked and don’t feel the need to defend themselves. Consider simply asking for what you want rather than telling people what they’re doing wrong, and see what happens.

I will admit, asking for what you want in a neutral and non-judgmental way when you’re frustrated is very hard to do. The antidote is to anticipate your needs and ask for what you want at the onset of anything new. And when things go awry, wait until you’re not upset to make a request. If you are critical, apologize and promise to do better next time. It’s all trial and error. And luckily, because most of us aren’t great at setting expectations and human beings are human and make mistakes, you’ll have lots and lots of chances to practice giving feedback and making requests.

I’ll never forget a coaching meeting I had about two years ago. I gave the manager I was coaching some tough feedback and he replied by saying, “I know I do that.” So I asked him, “If you know this is an issue, why are we having the discussion? He told me, “I just figured this is the way I am.” And I realized that knowing a behavior is ineffective doesn’t mean we know what to do to make things better.

I’ll never forget a coaching meeting I had about two years ago. I gave the manager I was coaching some tough feedback and he replied by saying, “I know I do that.” So I asked him, “If you know this is an issue, why are we having the discussion? He told me, “I just figured this is the way I am.” And I realized that knowing a behavior is ineffective doesn’t mean we know what to do to make things better.