Posts Tagged ‘candid culture’

I had a colleague at my last job, prior to starting Candid Culture, who was a peer and a friend. We were at a similar level and would periodically sit in one of our offices, with the door closed, talking about the bad decisions our company’s senior leaders made. One day I realized that these conversations were exhausting to me. They were negative and didn’t make me feel better. In fact, they made me feel worse.

Some people distinguish between office gossip and venting, asserting that venting is cathartic and makes people feel better. It doesn’t. Venting and office gossip are one in the same and both will make you tired and feel worse about your job and organization.

I’ll use an analogy from one of Deepak Chopra’s books. When you put a plant in the closet and don’t give it light or water, it withers and dies. When you put a plant in the sunlight and water it, it grows. And the same is true for people. Wherever you put your attention will get bigger and stronger. Whatever you deprive attention will become smaller.

In addition to draining you of energy and ensuring you focus on the things that frustrate you, office gossip destroys organizations’ cultures. If employees can’t trust that their peers won’t talk about them when they’re not there, there is no trust in the organization. And this lack of trust feels terrible. It makes employees nervous and paranoid. A lack of trust sucks the enjoyment out of working because we feel we have to continuously watch our back.

Office gossip isn’t going anywhere. It’s a human phenomenon and is here to stay. But you can reduce office gossip.

Here are five steps to reduce the office gossip in your workplace:

Reducing gossip in the workplace step one: Address the gossip head on.

Tell your employees, “I’ve been hearing a lot of gossip, which is not good for our culture.”

Reducing gossip in the workplace step two: Hold regular town hall meetings, and give employees more information than you think you need to about initiatives, organizational changes, profitability, etc. Employees want to know how the organization is doing. In the absence of knowledge, people make stuff up, not because they’re malicious, but because they have a need to know. Employees don’t have to fill in the gaps with office gossip when you inform them.

Reducing gossip in the workplace step three: Create a no-gossip-in-the-workplace practice and give employees the skills to have direct conversations.

Tell your employees, “We want people talking directly to each other, rather than about each other. As a result, we’re putting a no-gossip practice in place.” Then train employees throughout the organization how to give feedback that strengthens versus damages relationships.

Reducing gossip in the workplace step four: Draw attention to gossip.

Perhaps suggest, “Every time you hear gossip, wave two fingers in the air (or something else that’s equally visual).” This will draw attention to office gossip without calling anyone out.

Also, ask your peers and friends not to gossip with you. End conversations that contain gossip. This will be hard to do, but if everyone does it, it will become much easier.”

Reducing gossip in the workplace step five: Have an agreed-upon consequence for gossip.

Tell employees, “Every time we hear gossip in the workplace, the gossiper owes a dollar. Dollars go towards company happy hours and social events.”

The keys to reducing office gossip are to draw attention to the gossip, have a consequence for gossiping, and over communicate so your employees don’t have to fill in the gaps themselves.

Venting and office gossip are the same. If you’re talking about someone else and you’re not planning a conversation with a coworker or friend to address a challenge or problem, you’re gossiping. And talking about what frustrates you will only make you more frustrated.

My advice: Do something about the things you can impact and let the other stuff go. Talk about the things that matter to you. Resist the temptation to speak negatively about the people around you. And know that anyone who will gossip about someone to you, will also gossip about you.

The purpose of feedback isn’t to teach people a lesson, it’s to elicit certain behavior. Below are six strategies for giving helpful and succinct upgrade feedback:

- Write down your message. Save it as a draft. Re-read it later, when you’re not emotional, then cut the words in half. Shorter is better.

- Remove emotion. Examples are helpful, emotion is not. Emotion: You embarrassed me. Example: You raised your voice at me in front of others.

- Remove judgments. Vague words are judgmental. Judgment: Your behavior was unacceptable. Specific: You rolled your eyes at a coworker.

- When you can deliver your message in about a minute, without emotion or judgment, you’re ready to speak.

- Deliver all upgrade feedback in a private setting, behind a closed door.

- Then, let it go. When the conversation is over, it’s over. Don’t stay angry or remind the person of the situation. If the behavior is repeated, discuss it then.

Say only what you need to. Deliver messages privately. Protect the person’s ego, which is fragile. Let people save face.

This week’s blog is an excerpt from my book How to Say Anything to Anyone: A Guide for Building Business Relationships That Really Work. I hope it helps you have the conversations you need to have!

The Feedback Formula:

1. Introduce the conversation. Ask for time to talk, ensure the conversation is private, and it’s a good time for the feedback recipient.

2. Share your motive for speaking so both the feedback provider and the recipient feel as comfortable as possible.

3. Describe the observed behavior so the recipient can picture a specific, recent example of what you’re referring to. The more specific you are, the less defensive the listener will be, and the more likely they’ll be to hear you and take corrective action.

4. Sharing the impact or result describes the consequences of the behavior – what happened as a result of the person’s actions.

5. Having some dialogue gives both people a chance to speak and ensures the conversation is not one-sided. Many feedback conversations are not conversations at all – they’re monologues. One person talks and the other person pretends to listen, while thinking what an idiot you are. Good feedback conversations are dialogues during which the recipient can ask questions, share their point of view, and explore next steps.

6. Make a suggestion or request so the recipient has another way to approach the situation or task in the future. Most feedback conversations tell the person what they did wrong and the impact of the behavior – only rarely do they offer an alternative. Give people the benefit of the doubt. If people knew a better way to do something, they would do it another way.

7. Building an agreement on next steps ensures there is a plan for what the person will do going forward. Too many feedback conversations do not result in behavior change. Agreeing on next steps creates accountability.

8. Say “Thank you” to create closure and to express appreciation for the recipient’s willingness to have a difficult conversation.

If you’re giving more than one piece of feedback during a conversation, address each issue individually. For example, if you need to tell someone that they need to arrive on time and also check their work for errors, first go through the eight steps in the formula to address lateness. When you’ve discussed an agreement of next steps about being on time, go back to step three and address the errors. Talk about one issue at a time so the person clearly understands what they are supposed to do.

Here’s how a conversation could sound, using the eight-step Feedback Formula:

Before I started Candid Culture, I had a coworker who was a lingerer. Lisa would hover outside my office until there was an opportunity to interrupt. Lisa then walked in uninvited and started talking. I was still mid-thought about whatever I’d been working on and wasn’t ready to listen. After a few sentences, I would interrupt Lisa, saying, “I’m sorry. I don’t know what you’re talking about. Will you please start over?”

Embarrassing as it sounds, this went on for more than a year. I wanted to be seen as accessible and open, yet this “lingering” method of interrupting was driving me crazy. And it was a waste of both of our time. After many months of frustration, I decided to use The Feedback Formula.

Step One: Introduce the conversation.

“Lisa, I need to talk with you. When do you have about ten minutes of uninterrupted, private time?”

Step Two: Share your motive for speaking.

“There is something impacting me and our working relationship.”

Step Three: Describe the observed behavior.

“I’ve noticed that when you want to talk to me you stand at my door, waiting for a good time to interrupt. When you come into my office, you’re often in the middle of a thought or problem that you’ve probably been thinking about for a while.”

Steps Four and Six: Share the impact or result of the behavior and make a suggestion or request for what to do next time.

“Because I’m in the middle of something completely different, it takes me a few seconds to catch up. By the time I have, I’ve missed key points about your question, and I have to ask you to start over. This isn’t a good use of either of our time.

“Here is my request: When I’m in my office working and you need something, knock and ask if it’s a good time. If it is, I’ll say yes. Give me a few seconds to finish whatever I’m working on, so I’m focused on you when we start talking. I’ll tell you when I’m ready. Then start at the beginning, giving me a little background, so I have some context. And if it isn’t a good time for me, I’ll tell you that and come find you as soon as I can.”

Step Five: Have some dialogue. Allow the recipient to say whatever they need to say.

“What do you think?”

Step Seven: Agree on next steps.

“Okay, so next time you want to talk with me, you’re going to tap on the door and ask if it’s a good time to talk. If it’s not, I’ll tell you that and come find you as soon as I can. If it is a good time, you’re going to give me a second to finish whatever I’m working on and give me some background about the issue at hand. Does that work for you?”

We have just managed “the lingerer”—a challenge you probably have, unless you work from home 100% of the time or in a closet.

You may have noticed that I changed the order of The Feedback Formula during this conversation. It’s not the order of the conversation that’s important. It’s that you provide specific feedback, offer alternative actions, and have some dialogue before the conversation ends.

Summary: Effective feedback is specific, succinct, and direct.

Provided you have a trusting relationship with someone and have secured permission to give feedback, there is very little you can’t say in two minutes or less. The shorter and more direct the message, the easier it is to hear and act upon. Follow the eight-step Feedback Formula. Be empathetic and direct. Cite specific examples. Give the other person a chance to talk. Come to agreement about next steps. Remember, you do people a favor by being honest with them. People may not like what you have to say, but they will invariably thank you for being candid.

This week’s blog is an excerpt from my book How to Say Anything to Anyone: A Guide for Building Business Relationships That Really Work. I hope it helps you have the conversations you need to have! Be candid. You can do it!

Surveys are a great way to gather data. They’re not a great way to build relationships. In addition to sending out employee engagement surveys, ask questions live. Employees want to talk about their experience working with your organization, and employees will give you real, honest, and salient data, if you ask them and make it safe to tell the truth.

Here are a few methods of gathering data, in addition to sending employee engagement surveys:

Managers, ask questions during every one-on-one and team meeting with employees.

Managers, consider asking:

- What’s being talked about in the rumor mill?

- What do I need to know about that you suspect I don’t?

- What makes your job harder than it has to be? What would make your job easier?

- What meetings are not a good use of time?

Listen and be careful not to defend. Employees want to be heard. Respond if you’re able, but don’t deflect the feedback you receive.

Leaders, conduct roundtable discussions with small groups of employees throughout the year. I’d suggest discussions with groups of six employees. Have virtual or in-person lunch or coffee. Keep the meetings informal.

Leaders, consider asking:

- What’s a good decision we made in the last six months? What’s a decision we made that you question?

- Do you refer your friends to work here? If not, why not?

- What’s something happening in the organization that you’re concerned about?

How to Get the Truth:

- Ensure there are no negative consequences for people who tell you the truth.

- Give positive attention to the people who risk and give you negative information.

- Tell employees throughout the organization what you learn during these discussions and what you will and won’t be doing with the information. Share as much information as you can.

- You don’t need to act on every piece of data you receive. Just acknowledge what you heard and explain why you will or won’t be taking action.

Employees are loyal to managers and organizations they feel connected to, and connections are formed through conversations. So, in addition to sending employee engagement surveys, ask questions during every conversation and make it clear that you’re listening to the answers.

As someone who writes and teaches about effective communication in the workplace, I suspect the people I work and live with are expecting me to model good communication skills all the time. The good news: I try really hard to always do the right thing and impact people positively. The bad news, I’m human and sometimes I don’t get it right.

One of the things I’m proud of about Candid Culture, is that we are real people, working with real people. We work very hard to practice effective communication in the workplace and to always model what we’re teaching. And yet, like all people, we get busy, rushed, and tired. We read emails we intend to reply to but then forget to do so. We occasionally send emails, when we should pick up the phone.

In my world, a good communicator is not someone who always communicates perfectly.

A good communicator who practices effective communication in the workplace is someone who:

- Cares about people and consistently works to communicate in the way others need.

- Asks for and is open to feedback about how they impact people.

- Listens and watches other people’s verbal and non-verbal communication.

- Alters their communication style to meet other people’s needs.

- Takes responsibility when things don’t go well.

I advocate for picking up the phone, even when you want to do everything but, being patient, even when you’re frustrated, and asking questions, versus accusing. And I’m going to admit, I’m working to do these things too. Sometimes I get it right, and sometimes I don’t. I’m in the trenches with you, working to say and do the right things every day.

I promised you five tips to practice effective communication in the workplace and to be generous with people:

- Only call people when you have adequate time, attention, and patience to have whatever conversation needs to be had.

- If you need a few days to return a call, say so. Let the person know when you’ll call.

- Prepare for conversations. Plan what you’re going to say and how you’re going to say it.

- Don’t have hard conversations when you’re frustrated, tired, or busy. They won’t go well.

- If the conversation goes poorly, call back later and clean it up.

Being a good communicator doesn’t mean being perfect. It means caring enough to notice when you miss the mark, cleaning up your messes, and working to do it better next time. I’m working on the above recommendations too. And when I screw it up, you can be assured that my mistakes will become examples in our training programs of what not to do, followed by a new technique that will hopefully work for all of us.

Being in the wrong job feels terrible. It’s not unlike being in the wrong romantic relationship or group of friends. We feel misplaced. Everything is a struggle. Feeling like we don’t fit and can’t be successful is one of the worst feelings in the world.

The ideal situation is for an underperforming employee to decide to move on. But when this doesn’t happen, managers need to help employees make a change.

The first step in helping an underperforming employee move on to something where they can be more successful is to accept that giving upgrade (negative) feedback and managing employee performance is not unkind. When managers have an underperforming employee, they often think it isn’t nice to say something. Managers don’t want to hurt employees’ feelings or deal with their defensive reactions. When we help someone move on to a job that they will enjoy and where they can excel, we do the employee a favor. We set them free from a difficult situation that they were not able to leave out of their own volition.

I get asked the question, “How do I know when it’s time to let an employee go?” a lot.

Here’s what I teach managers in our coaching training program. There are four reasons employees don’t do what they need to do:

- They don’t know how.

- They don’t think they know how.

- They don’t want to.

- They can’t. Even with coaching and training, they don’t have the ability to do what you’re asking.

Numbers one and two are coachable. With the right training and coaching, employees will likely be able to do what you’re asking them to do.

Giving consistent feedback works well for number three.

Number four is not coachable. No amount of training, coaching, or feedback will make a difference.

When you’re confronted with someone who simply can’t do what you need them to do, it’s time to help the person make a change.

The way you discover whether or not someone can do something is to:

- Set clear expectations

- Observe performance

- Train, coach, and give feedback

- Repeat

After you’ve trained, coached, and given feedback for a period of time, and the person still can’t do what you’re asking them to do, it’s time to make a change.

Making a change does not mean firing someone. You have options:

- Take away responsibilities the person can’t do well and give them responsibilities they can do well.

- Rotate the person to a different job.

Firing someone is always a last resort.

Sometimes we get too attached to job descriptions. When the job description outlines a specific responsibility that the person can’t do, we fire the person versus considering who else in the organization could do that task? Be open-minded. If you have a person who is engaged, committed, and able to do most of their job, be flexible and creative. Swap responsibilities, when you can. Employees who are failing in one job, may do very well in a different job.

If you’ve stripped away the parts of a job an underperforming employee can’t do well, and the person is still not performing – it’s time to make a change. This is a difficult conversation that no manager wants to have. Yet I promise you, this conversation feels better to your employee than suffering in a job in which they can’t be successful. After you’ve set expectations, observed performance, and coached and given feedback repeatedly, letting someone go or rotating to the person to a different role is kinder than letting the employee flounder in a job in which they cannot be successful.

The fear of saying what we think and asking for what we want at work is prevalent across organizations. We want more money, but don’t know how to ask for it. We want to advance our careers but are concerned about the impression we’ll make if we ask for more. Many employees assume they won’t get their needs met and choose to leave their jobs, either physically or emotionally, rather than make requests.

How to Retain Good Employees:

The key to keeping your best employees engaged and doing their best work, is to ask more questions and make it safe to tell the truth.

Managers:

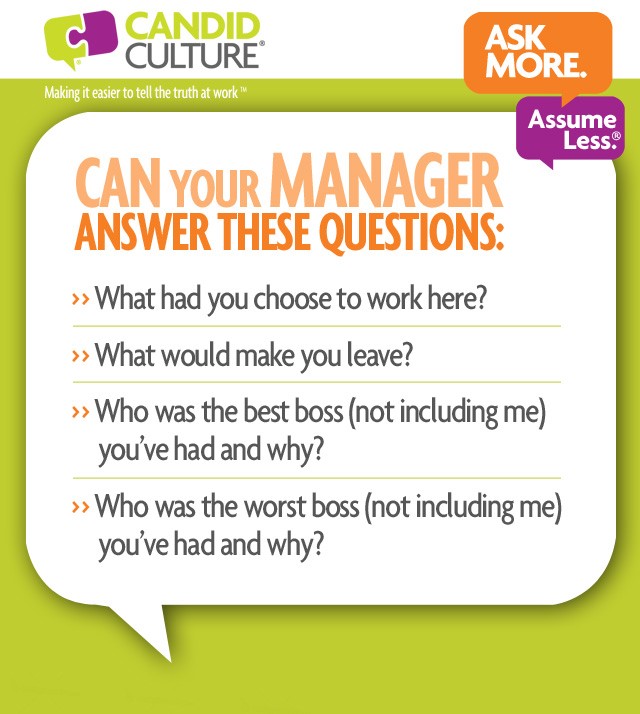

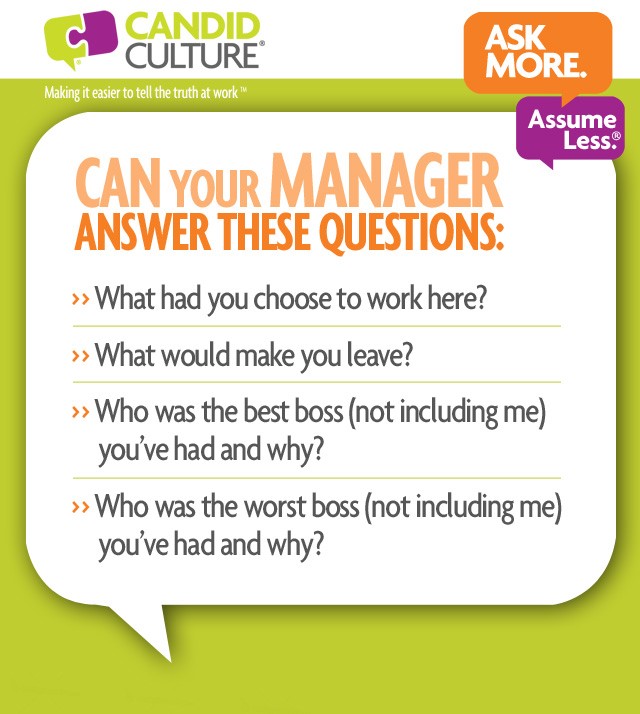

- Do you know why your employees chose your organization and what would make them leave?

- Do you know your employees’ best and worst boss?

The answers to these questions tells managers what employees need from the organization, job, and from the manager/employee working relationship.

Team members:

Can your manager answer these questions – that I call Candor Questions – about you? For most people, the answer is no. Most managers don’t ask these questions. And most employees are not comfortable giving this information, especially if the manager hasn’t asked for it.

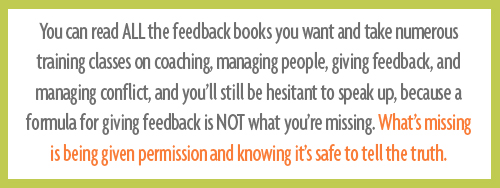

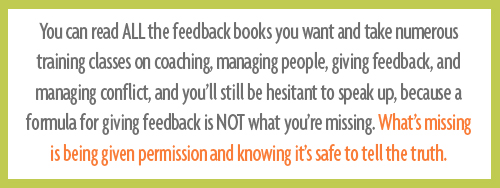

It’s easy to mistake my book, How to Say Anything to Anyone, as a book about giving feedback. It’s not. It takes me nine chapters to get to feedback. The first eight chapters of the book are about how to create relationships in which you can tell the truth without fear. You can read all the feedback books you want and take numerous training classes on coaching, managing people, giving feedback, and managing conflict, and you’ll still be hesitant to speak up, because a formula for giving feedback is not what you’re missing. What’s missing is being given permission and knowing it’s safe to tell the truth.

Managers, here’s how to retain good employees:

Tell your employees, “I appreciate you choosing to work here. I want this to be the best career move you’ve made, and I want to be the best boss you’ve had. I don’t want to have to guess what’s important to you. I’d like to ask you some questions to get to know you and your career goals better. Please tell me anything you’re comfortable saying. And if you’re not comfortable answering a question, just know that I’m interested and I care. And if, at any point, you’re comfortable telling me, I’d like to know.”

Then ask the Candor Questions during job interviews, one-on-one, and team meetings. We’re always learning how to work with people, so continue asking questions throughout your relationships. These conversations are not one-time events.

Then ask the Candor Questions during job interviews, one-on-one, and team meetings. We’re always learning how to work with people, so continue asking questions throughout your relationships. These conversations are not one-time events.

If you work for someone who isn’t asking you these questions, offer the information. You could say:

“I wanted to tell you why I chose this organization and job, and what keeps me here. I also want to tell you the things I really need to be happy and do my best work. Is it ok if I share?”

Your manager will be caught off guard, but it is likely that they will also be grateful. It’s much easier to manage people when you know what they need and why. Most managers want this information, it just may not occur to them to ask.

If the language above makes you uncomfortable, you can always blame me. You could say:

“I read this blog and the author suggested I tell you what brought me to this organization and what I really need to be happy here and do my best work. She said I’d be easier to manage if you had that information. Is it ok if I share?”

Yes, this might feel a little awkward at first, but the conversation will flow, and both you and your manager will learn a great deal about each other.

The ability to tell the truth starts with asking questions, giving people permission to speak candidly, and listening to the answers.

The people you work with want to do a good job. They want you to think highly of them. Yes, even the people you think do little work. Give people the benefit of the doubt. Assume people are doing their best. And when you don’t get what you want, make requests.

There are two ways to give feedback and get your needs met at work. You can give direct feedback, or you can ask for what you want.

Version one – give direct feedback: “You did this thing and here’s why it’s a problem.”

Version two is less direct. Rather than telling the person what went wrong, simply make a request.

Version two – ask versus tell: “Will you…” Or, “It would be helpful to get this report on Mondays instead of Wednesday. Are you able to do that?”

It’s very difficult to give feedback directly without the other person feeling judged. Making a request is much more neutral than giving direct feedback, doesn’t evoke as much defensiveness, and achieves the same result. You still get what you want.

When I teach giving feedback, I often give the example of asking a waitstaff in a restaurant for ketchup. Let’s say your waiter comes to your table to ask how your food is, and your table doesn’t have any ketchup.

Option one: Give direct feedback. “Our table doesn’t have any ketchup.”

Option two: Make a request. “Can we please get some ketchup?”

Both methods achieve the desired result. Option one overtly tells the waiter, “You’re not doing your job.” Option two still tells the waiter he isn’t doing his job, but the method is more subtle and thus is less likely to put him on the defensive.

You are always dealing with people’s egos. And when egos get bruised, defenses rise. When defenses rise, it’s hard to have a productive conversation. People stop listening and start defending themselves. Defending oneself is a normal and natural reaction to negative feedback. It’s a survival instinct.

You’re more likely to get what you want from others when they don’t feel attacked and don’t feel the need to defend themselves. Consider simply asking for what you want, rather than telling people what they’re doing wrong, and see what happens.

I will admit, asking for what you want in a neutral and non-judgmental way when you’re frustrated is very hard to do. The antidote is to anticipate your needs and ask for what you want at the onset of anything new. And when things go awry, wait until you’re not upset to make a request. If you are critical, apologize and promise to do better next time. Communication is all trial and error.

People don’t like the phrase “negative feedback” because it is, well, negative. So, someone came up with “constructive feedback”, i.e., “I have some constructive feedback for you.” I don’t particularly like that either. The definition of constructive is useful, and I think all feedback should be useful. I like the word “upgrade” instead. Upgrade implies the need for improvement, but it isn’t negative. The question is, which comes first, positive or upgrade feedback?

I always give positive feedback first. Not to make people feel better, but to ensure they hear the positive feedback. Most people want to be perfect. We want others to think well of us. Negative feedback calls our perfection into question and thus is hard to hear. When people get negative feedback, they naturally become defensive. It’s hard to listen when you’re defending yourself. If positive feedback comes after negative feedback, the positive feedback isn’t even heard. The negative feedback is all consuming.

When giving feedback, I tell people, “I have positive and upgrade feedback for you today. I’m going to give you the positive feedback first.” I give positive feedback, then I give upgrade feedback, and then I remind the person about the positive feedback, because I know the person is now consumed thinking about the negative feedback.

Think about yourself. If you receive seven pieces of positive feedback and one piece of upgrade feedback, what do you think about for the rest of the day? If you’re like most people, the rest of your day is about the upgrade feedback. We want to do good work and be thought well of, and negative feedback calls all of that into question and is thus, hard to hear.

Give positive feedback first, then give upgrade feedback, then remind the person about the positive feedback. People can handle feedback when it’s delivered by a trusted person in an objective way.

You will be passed over for jobs, projects, and opportunities, and never know why. Being passed over isn’t necessarily a bad thing, not knowing why you were passed over is problematic. If you don’t know why you’re being passed over, how can you be prepared next time?

Organizations are political. People talk. You’ve undoubtedly already experienced this.

If you want to manage your professional reputation, one thing you must know is who talks about you and what they say. How decisions get made in organizations isn’t always obvious. There are the obvious channels of decision making, like your boss and your boss’s boss. But there are also the people who talk to your boss and boss’s boss and have an opinion about you, who you may not be aware of.

Everyone in an organization has people they trust, who they listen to and confide in. Who those trusted people are isn’t always obvious. When you’re being considered for a new position or project, the decision makers will invariably ask others for their opinion. Knowing who does and doesn’t support you in a future role is essential to managing your professional reputation and career.

I don’t want you to be nervous, paranoid, or suspicious at work. I do want you to be savvy, smart, and aware.

It’s not difficult to find out who can impact your professional reputation at work, you just need to ask the people who know. Start with your manager. Your manager likely knows and will tell you, if you ask.

To ensure you know who can impact your professional reputation, tell your manager:

“I really enjoy working here. I enjoy the people, the work and our industry. I’m committed to growing my career with this organization.”

Then ask two or three of these questions:

- Who in the organization should I have a good relationship with?

- Who/what departments should I be working closely with?

- Who impacts my professional reputation and the opportunities I have?

- What skills do I have that the organization values most?

- What contributions have I made that the organization values most?

- What mistakes have I made from which I need to recover?

Your manager doesn’t walk around thinking about the answers to these questions. If you want thoughtful answers, set a time to meet with your manager. Tell your manager the purpose of the meeting – to get feedback on your professional reputation so you can adeptly manage your career – and send the questions in advance, giving your manager time to prepare for the meeting. You will get more thoughtful and complete answers if your manager has two weeks to think about the questions and ask others for input.

Don’t be caught off guard by a less-than-stellar professional reputation. Take control of your reputation and career. Ask more. Assume less.