Managing People Archive

Most people would rather get a root canal than participate in an annual employee performance appraisal.

The reasons employee performance appraisals are so difficult is simple:

- Many managers don’t deliver timely and balanced feedback throughout the year.

- Many employees don’t ask for regular feedback.

- Too much information is delivered during the annual employee performance appraisal.

- And as crazy as it sounds, managers and employees haven’t agreed to give and receive regular and candid feedback.

Here are four steps to ensure employee performance appraisals are useful and positive:

- Managers and employees must agree to give and receive balanced, candid feedback. Don’t assume the agreement to speak honestly (throughout the year) is implicit, make it explicit.

- Managers, be honest and courageous. Don’t rate an employee a five who is really a three. You don’t do anyone any favors. Employees want to know how they’re really doing, no matter how much the feedback may sting.

- Managers, focus on three things the employee did well and three things to do more of next year. Any more input is overwhelming.

- Managers, schedule a second conversation a week after the employee performance appraisal, so employees can think about and process what you’ve said and discuss further, if necessary.

The key to being able to speak candidly during an employee performance appraisal is as simple as agreeing that you will do so and then being receptive to whatever is said. And don’t make feedback conversations a one-time event. If you do a rigorous workout after not exercising for a long time, you often can’t move the next day. Feedback conversations aren’t any different. They require practice for both the manager and employee to be comfortable. Speak regularly, even just for a few minutes. And remember, the right answer to feedback, in the moment, is “thank you.” Make it easy to tell you the truth.

When something ‘bad’ happens, my nine-year-old is quick to ask who is at fault, hoping, of course, it’s not him. I’m trying to get him to use the word accountability instead, and to understand that if he has some accountability, he has some control over what happens. If he has no accountability, he has no control. A tough concept for a nine-year-old.

Stuff happens. People won’t give you what you need to complete projects. Things will break. When breakdowns happen, I always ask myself, “What could I have done to prevent this situation?” or “What did I do to help create this situation?”

It may sound odd that I always look at myself when breakdowns occur, even when it’s someone else who didn’t do their job. It’s just easier. When I can identify something I could have done to make a situation go differently, I feel more in control – aka better.

I’m the person who gets off a highway jammed with traffic. The alternative route may end up taking longer, but at least I’m moving. I feel like I’m doing something and thus have more control. Taking responsibility for what happens to you is similar. When you’re accountable for what happens, you can do something to improve your situation. When someone else is accountable, you’re at the mercy of other people and have very little control.

There are, of course, exceptions to the practice that “we’re accountable.” Terrible and unfair acts of violence, crime, and illness happen to people, about which they have no control. But in general, in our day-to-day lives, there is typically something we did to contribute to a bad situation or something we can do to improve it.

Here are four practices for improving difficult situations even when you didn’t create the mess alone.

- Ask more questions. If you’re not clear as to what someone is expecting from you, ask. Even if their instructions aren’t clear, it is you who will likely be held accountable later.

- Tell people what you think they’re expecting and what you’re planning to do, to ensure everyone’s expectations are aligned. This beats doing weeks’ worth of work, only to discover what you created isn’t what someone else had it mind.

- Ask for specific feedback as projects progress. Don’t wait until the end of a project to find out how you performed.

- Admit when you make a mistake or when you wish you had done something differently. Don’t wait for someone to tell you. Saying, “I’m sorry. How can I make this right with you?” goes a long way.

These are really delegation practices — reverse delegation. Help people express their expectations of you clearly, so you can be successful.

I am always asking the questions, “What could I have done differently? What did I do to contribute to this situation, what can I do now to make this situation better?” I encourage you to do the same, even when someone else drops the ball. You can’t control others, but you can control you. And your happiness and success is your responsibility.

Leaders with virtual and hybrid workforces are worried about losing their organization’s culture. Some organizations are calling employees back into the office to retain culture. Others are hosting in-person social events, retreats, and meetings to help employees reconnect and strengthen culture.

Getting together in person is nice but it isn’t always possible. And what happens when everyone goes home? Culture is built on a daily basis.

Organizational culture is an outcome of the decisions we make and how those decisions get made, how we treat people, and how we communicate and work together. If you want to strengthen your organization’s culture, do it every day.

To strengthen your culture, take small regular actions.

Start each meeting helping employees get to know each other better, from a work perspective.

Host town halls at least twice a year.

Host roundtable discussions between senior leaders and a diverse sample of your workforce.

Have leaders and managers leave employees a weekly voicemail. Share a recent success, challenge, or goal. Keep messages short and authentic. Set the tone for the week.

All of these actions can be done virtually or in a hybrid setting.

Give employees opportunities to talk to each other about the things that matter most at work. Do this regularly – at least a few times a year.

You don’t need to spend a lot of money to strengthen and retain your culture. Go small – regularly.

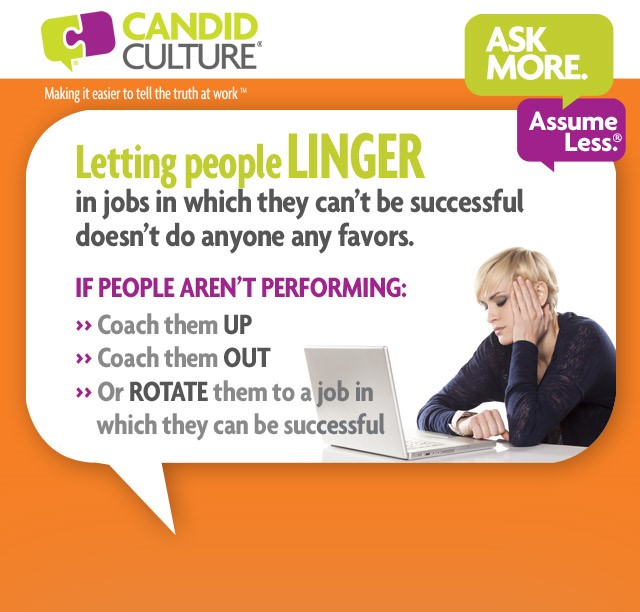

Being in the wrong job feels terrible. It’s not unlike being in the wrong romantic relationship or group of friends. We feel misplaced. Everything is a struggle. Feeling like we don’t fit and can’t be successful is one of the worst feelings in the world.

The ideal situation is for an underperforming employee to decide to move on. But when this doesn’t happen, managers need to help employees make a change.

The first step in helping an underperforming employee move on to something where they can be more successful is to accept that giving upgrade (negative) feedback and managing employee performance is not unkind. When managers have an underperforming employee, they often think it isn’t nice to say something. Managers don’t want to hurt employees’ feelings or deal with their defensive reactions. When we help someone move on to a job that they will enjoy and where they can excel, we do the employee a favor. We set them free from a difficult situation that they were not able to leave out of their own volition.

I get asked the question, “How do I know when it’s time to let an employee go?” a lot.

Here’s what I teach managers in our coaching training program. There are four reasons employees don’t do what they need to do:

- They don’t know how.

- They don’t think they know how.

- They don’t want to.

- They can’t. Even with coaching and training, they don’t have the ability to do what you’re asking.

Numbers one and two are coachable. With the right training and coaching, employees will likely be able to do what you’re asking them to do.

Giving consistent feedback works well for number three.

Number four is not coachable. No amount of training, coaching, or feedback will make a difference.

When you’re confronted with someone who simply can’t do what you need them to do, it’s time to help the person make a change.

The way you discover whether or not someone can do something is to:

- Set clear expectations

- Observe performance

- Train, coach, and give feedback

- Repeat

After you’ve trained, coached, and given feedback for a period of time, and the person still can’t do what you’re asking them to do, it’s time to make a change.

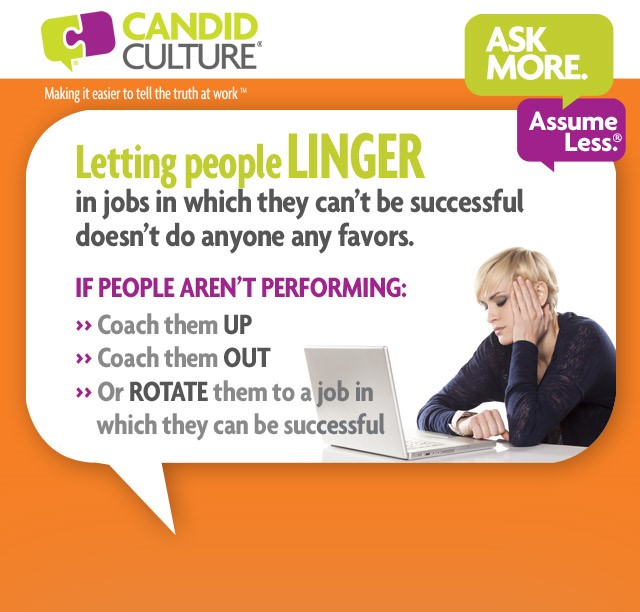

Making a change does not mean firing someone. You have options:

- Take away responsibilities the person can’t do well and give them responsibilities they can do well.

- Rotate the person to a different job.

Firing someone is always a last resort.

Sometimes we get too attached to job descriptions. When the job description outlines a specific responsibility that the person can’t do, we fire the person versus considering who else in the organization could do that task? Be open-minded. If you have a person who is engaged, committed, and able to do most of their job, be flexible and creative. Swap responsibilities, when you can. Employees who are failing in one job, may do very well in a different job.

If you’ve stripped away the parts of a job an underperforming employee can’t do well, and the person is still not performing – it’s time to make a change. This is a difficult conversation that no manager wants to have. Yet I promise you, this conversation feels better to your employee than suffering in a job in which they can’t be successful. After you’ve set expectations, observed performance, and coached and given feedback repeatedly, letting someone go or rotating to the person to a different role is kinder than letting the employee flounder in a job in which they cannot be successful.

The fear of saying what we think and asking for what we want at work is prevalent across organizations. We want more money, but don’t know how to ask for it. We want to advance our careers but are concerned about the impression we’ll make if we ask for more. Many employees assume they won’t get their needs met and choose to leave their jobs, either physically or emotionally, rather than make requests.

How to Retain Good Employees:

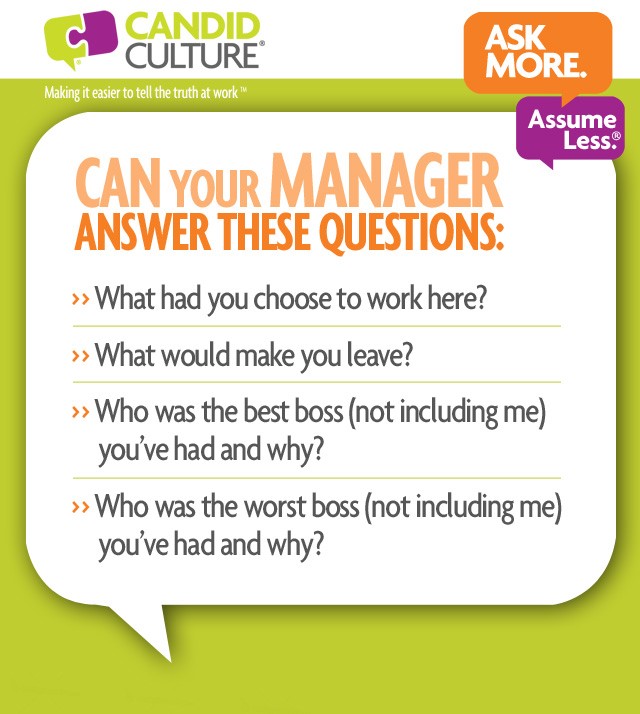

The key to keeping your best employees engaged and doing their best work, is to ask more questions and make it safe to tell the truth.

Managers:

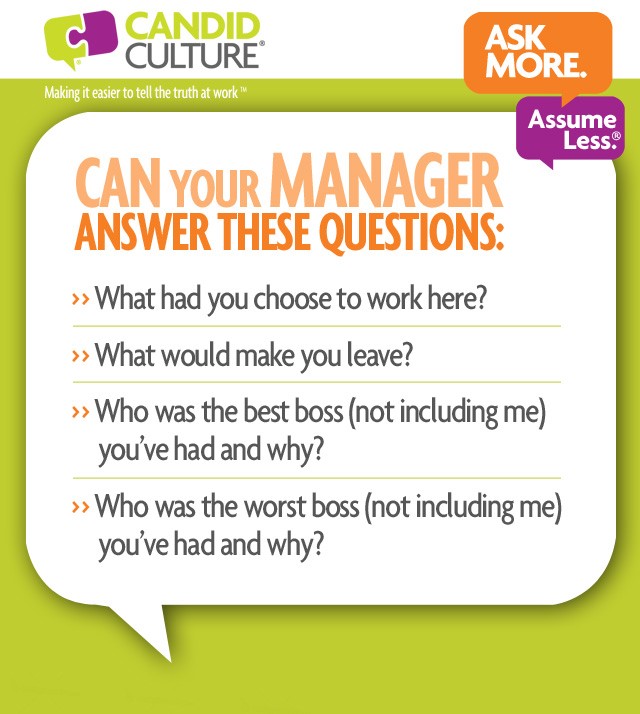

- Do you know why your employees chose your organization and what would make them leave?

- Do you know your employees’ best and worst boss?

The answers to these questions tells managers what employees need from the organization, job, and from the manager/employee working relationship.

Team members:

Can your manager answer these questions – that I call Candor Questions – about you? For most people, the answer is no. Most managers don’t ask these questions. And most employees are not comfortable giving this information, especially if the manager hasn’t asked for it.

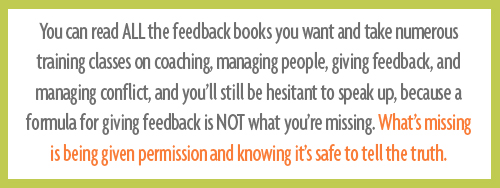

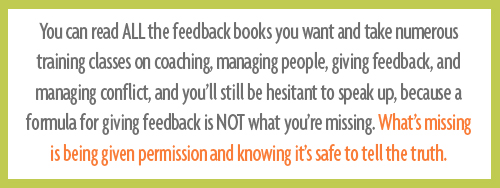

It’s easy to mistake my book, How to Say Anything to Anyone, as a book about giving feedback. It’s not. It takes me nine chapters to get to feedback. The first eight chapters of the book are about how to create relationships in which you can tell the truth without fear. You can read all the feedback books you want and take numerous training classes on coaching, managing people, giving feedback, and managing conflict, and you’ll still be hesitant to speak up, because a formula for giving feedback is not what you’re missing. What’s missing is being given permission and knowing it’s safe to tell the truth.

Managers, here’s how to retain good employees:

Tell your employees, “I appreciate you choosing to work here. I want this to be the best career move you’ve made, and I want to be the best boss you’ve had. I don’t want to have to guess what’s important to you. I’d like to ask you some questions to get to know you and your career goals better. Please tell me anything you’re comfortable saying. And if you’re not comfortable answering a question, just know that I’m interested and I care. And if, at any point, you’re comfortable telling me, I’d like to know.”

Then ask the Candor Questions during job interviews, one-on-one, and team meetings. We’re always learning how to work with people, so continue asking questions throughout your relationships. These conversations are not one-time events.

Then ask the Candor Questions during job interviews, one-on-one, and team meetings. We’re always learning how to work with people, so continue asking questions throughout your relationships. These conversations are not one-time events.

If you work for someone who isn’t asking you these questions, offer the information. You could say:

“I wanted to tell you why I chose this organization and job, and what keeps me here. I also want to tell you the things I really need to be happy and do my best work. Is it ok if I share?”

Your manager will be caught off guard, but it is likely that they will also be grateful. It’s much easier to manage people when you know what they need and why. Most managers want this information, it just may not occur to them to ask.

If the language above makes you uncomfortable, you can always blame me. You could say:

“I read this blog and the author suggested I tell you what brought me to this organization and what I really need to be happy here and do my best work. She said I’d be easier to manage if you had that information. Is it ok if I share?”

Yes, this might feel a little awkward at first, but the conversation will flow, and both you and your manager will learn a great deal about each other.

The ability to tell the truth starts with asking questions, giving people permission to speak candidly, and listening to the answers.

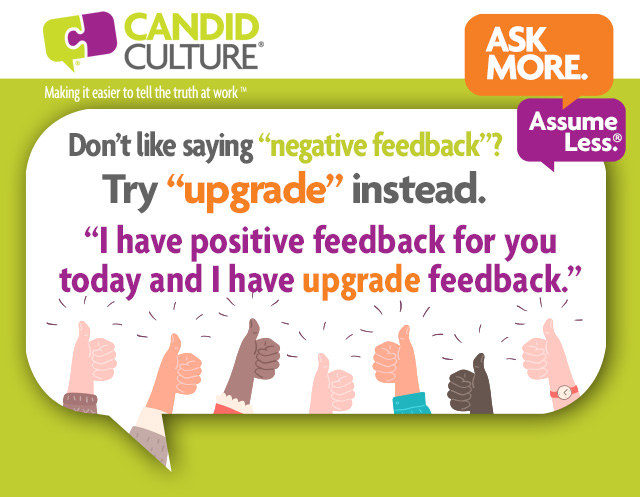

People don’t like the phrase “negative feedback” because it is, well, negative. So, someone came up with “constructive feedback”, i.e., “I have some constructive feedback for you.” I don’t particularly like that either. The definition of constructive is useful, and I think all feedback should be useful. I like the word “upgrade” instead. Upgrade implies the need for improvement, but it isn’t negative. The question is, which comes first, positive or upgrade feedback?

I always give positive feedback first. Not to make people feel better, but to ensure they hear the positive feedback. Most people want to be perfect. We want others to think well of us. Negative feedback calls our perfection into question and thus is hard to hear. When people get negative feedback, they naturally become defensive. It’s hard to listen when you’re defending yourself. If positive feedback comes after negative feedback, the positive feedback isn’t even heard. The negative feedback is all consuming.

When giving feedback, I tell people, “I have positive and upgrade feedback for you today. I’m going to give you the positive feedback first.” I give positive feedback, then I give upgrade feedback, and then I remind the person about the positive feedback, because I know the person is now consumed thinking about the negative feedback.

Think about yourself. If you receive seven pieces of positive feedback and one piece of upgrade feedback, what do you think about for the rest of the day? If you’re like most people, the rest of your day is about the upgrade feedback. We want to do good work and be thought well of, and negative feedback calls all of that into question and is thus, hard to hear.

Give positive feedback first, then give upgrade feedback, then remind the person about the positive feedback. People can handle feedback when it’s delivered by a trusted person in an objective way.

Hire people using whatever legal criteria you like. Compensate employees however you like. Charge for your products and services however you like. Run your business however you like. But be transparent about your practices. People want to work with those they trust. Transparency builds leadership trust.

A few weeks ago, one of our vendors gave me a bill that was higher than what I expected, so I asked for an itemized invoice. I never heard from the company again. Poof: they disappeared. Not a great way to build leadership trust nor a reputation.

Another vendor was very delayed in filling our product orders. When I asked questions about how such a thing could happen, I got a vague answer. “I guess we have communication issues, and you got lost in the shuffle.” It was an insufficient and thus bad answer that didn’t instill confidence in the company. Instead, it created doubt that they could reliably meet our needs, and we’re going to replace them.

One of my friends recently got turned down for an internal job. She was told, “You’re just not the right fit – an unhelpful and yet typical way to decline an internal candidate.

You don’t owe your employees or customers answers, but if you want people to want to work with you, have confidence in you, and trust you, you’ll provide more information than you think you need to.

Employees and customers can handle the truth. And while you may not think you need to provide it, people want to work with those they trust. We trust people who give us the whole truth, or at least more of it than, “I guess you got lost in the shuffle.”

Increase business trust: Be clear and transparent about your pricing.

Increase corporate trust: Tell employees how and why you make the hiring decisions you do. They’ll refer friends to work for you, even when you decline them.

Increase leadership trust: Tell employees how the organization makes money, the feedback you’re getting from prospects and customers, and why you’re making the business decisions you’re making. Employees will feel more connected and thus committed to the organization.

Knowledge makes people feel comfortable. The people who work for and with you want to understand how and why decisions are made. If you want your customers and employees to trust you, give them a little more truth than you might think necessary.

When the people we work with don’t do their jobs, we might find ourselves saying, “They should be more on top of things.” “They shouldn’t make commitments they can’t keep.” “They don’t know what they’re doing, and that’s not my problem.” The challenge is, when your coworkers don’t perform, it is your problem.

When your coworkers don’t get you the information you need in a timely way, you miss deadlines. When you work from incorrect information, your reports are wrong. When others don’t work with you, you look bad. So, you can be right all day about how others perform, and your reputation will still be negatively impacted.

I don’t suggest you enable your coworkers by doing the work others don’t. I do suggest you help your coworkers be successful by holding them accountable.

Here are a few things you can do to manage your career and get what you need from your business relationships:

- Don’t assume others will meet deadlines. Check in periodically and ask, “What’s been done so far with the XYZ project?” Notice, I didn’t suggest asking, “How are things going with the XYZ project.” “How are things going” is a greeting, not a question.

- Set iterative deadlines. If August 25th is your drop-dead deadline, ask to see pieces of work incrementally. “Can I see the results of the survey on August 10th, the write-up on August 15th, and the draft report on August 20th?” One of the biggest mistakes managers and project managers make is not practicing good delegation by setting iterative deadlines and reviewing work as it’s completed.

- Don’t just email and ask for updates. The people you work with are overwhelmed with email, and email is too passive. Visit people’s offices or pick up the phone.

You might be thinking, “Holding my coworkers accountable is awkward. I don’t have the formal authority, and I don’t want my coworkers to think I’m bossy or damage my business relationships.”

It’s all in the how you make requests.

If you’ve seen me speak or have read the business book How to Say Anything to Anyone, you know I believe in setting clear expectations at the beginning of anything new. That could sound something like, “I’m looking forward to working with you on the XYZ project. How would you feel if we set iterative deadlines, so we can discuss work as it is completed? You’ll get just-in-time input, making any necessary adjustments as we go, and we’ll stay ahead of schedule. How does that sound? How are the 10th, 15th, and 20th as mini deadlines for you?”

Many people put large projects off until the last minute. People procrastinate less when large projects are broken into smaller chunks with correlating deadlines. You strengthen your business relationships and support people in meeting deadlines and not procrastinating when you agree on completion dates when projects begin. Also, most of us unfortunately know what it’s like to put a lot of work into a project, have someone review our completed work, and then be told we went down the wrong path and need to start over.

Ask more. Assume less. Don’t assume your coworkers will do what they’re supposed to do. Ask upfront to see pieces of work on agreed-upon dates. Pick up the phone versus rely on email to communicate and know that the people you work closely with are a reflection of you. Get people working with you, and everyone will look good.

Many years ago, before starting Candid Culture, during my annual performance review, my manager said, “You had a great year. You rolled out 18 new training programs and got more participation in those programs than we’ve ever seen in the past. But you’re all substance and no sizzle. You’re not good at sharing the work you’re doing, and as a result my boss doesn’t know enough about what you’re doing to support a significant salary increase for you, so I can’t even suggest one.”

That happened to me ONCE, and I swore it would never happen again.

Too many people believe that if they do good work, the right people will notice, and they will be rewarded appropriately. Part of this thinking is accurate. To be rewarded appropriately, you need to be doing good work. But the people in a position to reward you also need to know what you’re doing and the value you’re adding.

You need to find a way to share the value you’re providing without going over your boss’s head, sucking up, or alienating your coworkers.

Here are three ways to manage up while strengthening your business relationships.

All of these practices work whether you’re working virtually, hybrid, or in the office full-time.

Manage up tip number one: Ask your manager’s permission to send them a monthly update of what you accomplished during the month. The update should be a one-page, easy-to-read, bulleted list of accomplishments or areas of focus.

Your boss is busy doing their own work. As a result, you need to let managers know about the work you’re doing. Don’t make them guess.

Manage up tip number two: Periodically share what you’re doing with the people your manager works for and with. That can sound like, “I just wanted to share what my department is accomplishing. We’re really excited about it.” Ask your manager’s permission to do this and tell them why you want to do it (to ensure that the senior people in your organization are in-the-know about what your department’s accomplishments).

If you’re not sure who can impact your career and thus who you should inform about your work, ask your manager. Managers know and will tell you, if you ask.

Manage up tip number three: Use the word “we” versus “I.” “We accomplished…..” “We’re really excited about….” Using the word “we” is more inclusive and makes you sound like a team player versus a lone ranger.

Don’t assume people know what you’re doing or the value you’re adding to your organization. Instead, assume people have no idea and find appropriate ways to tell them. You are 100% accountable for your career.

There are three reasons people say “that’s above or below my paygrade” or “that’s not my job” – they don’t feel empowered to make decisions, they think they’re being unfairly compensated for the challenges at hand, or they aren’t particularly motivated.

“That’s not my job” (aka, I don’t do things that are outside of my job description) is a mindset, and if someone has it, I’d suggest not hiring that person. People who think they should only have to do what’s on their job description aren’t utility players, and your organization is likely too lean to afford employees who only want to perform in a narrow box.

“That’s not my job” can also be an outcome of leaders and managers who can’t let go and let employees take risks and make decisions. If that’s your management style, hire people who will follow directions and don’t want to create new things and solve problems. Problem solvers will be frustrated if they only get to follow instructions.

Here are six steps to steer clear of “that’s not my job” syndrome and advance your career, regardless of your current role in your organization:

- Never say the words “that’s above or below my paygrade” or “that’s not my job.” Even if it’s true.

- If you don’t have the latitude to solve certain problems, ask the people you work for how they want you to handle those types of issues when you see or hear about them. That’s a subtle way to provide feedback that you don’t have the latitude you need to solve certain problems.

- When you see an impending train wreck, say something. I see lots of very capable employees see the train wreck coming, comment to themselves or others who can’t do anything about the problem (aka gossip), and then nod knowingly when the *&#@ hits the fan. Don’t be that person. Look out for your organization and the people you work with.

- If you see a broken or lacking process, raise the issue with someone who can do something about it, and offer to take a stab at fixing the problem. One of managers’ biggest complaints is employees who dump and run – “I’ve identified a problem. I’m leaving it for you to fix.”

- Go out of your way to do the right thing, even if you are uncomfortable or don’t want to. If it’s easier to email someone, but you know the right thing to do is to pick up the phone, pick up the phone. If an internal or external customer express concerns and you can’t solve the problem, find someone who can. There are lots of ways to make an impact.

- Ask more questions. Find a non-judgmental way to ask, “Why do we do this this way?” “Have we considered…?” “Would you be open to trying…?” Status quo can be the right thing and what’s necessary. It can also be the death of organizations.

Make stuff happen. Don’t pass the buck. And if you are going to pass the buck, don’t announce it. It only makes you look disempowered and uncommitted.