Giving Feedback – 3 Funny Examples of Giving Employee Feedback

Get the words to say the hardest things in two minutes or less. If you work long enough, you’ll eventually be confronted with these situations. Giving feedback doesn’t have to be hard.

Get the words to say the hardest things in two minutes or less. If you work long enough, you’ll eventually be confronted with these situations. Giving feedback doesn’t have to be hard.

Many people struggle to say no. As a result, when someone has a request that we can’t or don’t want to meet, we often say nothing. We simply don’t respond. Or we put the person off telling them we’ll get back to them. Then people wonder. “Did they get my request? Should I send the request again? Will I look bad if I ask again? How many times should I ask before I just let the request go?”

Saying no is better than saying nothing. No gives people closure. Silence leaves people in limbo wondering what they should do next.

Saying no is hard. We don’t want to disappoint or let people down. And yet, you can’t say yes to everything. You can say no and still sound like a responsible, easy-to-work-with, accommodating professional.

Here are ways to say no:

Saying “thank you” acknowledges the other person and buys you time to think about their request.

You don’t need to reply in the moment. I often regret things I agree to without thinking through the request thoroughly.

How to Say No Option One: Simply say no.

Example: “I really appreciate you asking me to write the proposal for the __________ RFP. I’m not able to do that. Can I recommend someone else who has the expertise and time to do a great job?”

Don’t give a bunch of reasons for saying no. People aren’t interested in why we can or can’t do something; they just want to know if we will do it.

How to Say No Option Two: Agree and negotiate the time frame.

Example: “I’d be happy to do that. I can’t do it before the last week of the month. Would that work for you?” If the answer is no, negotiate further. Ask, “When do you really need it? I can certainly do pieces by then, but not the whole thing. Given that I can’t meet your timeline, who else can work on this in tandem or instead of me?”

How to Say No Option Three: Say no to the request but say what you can do.

Example: “I can’t do _______. But I can do ________. How would that work?”

A review of how to say no:

Saying no is always hard. But it’s always better to say no than to ignore requests, or to say yes and do nothing.

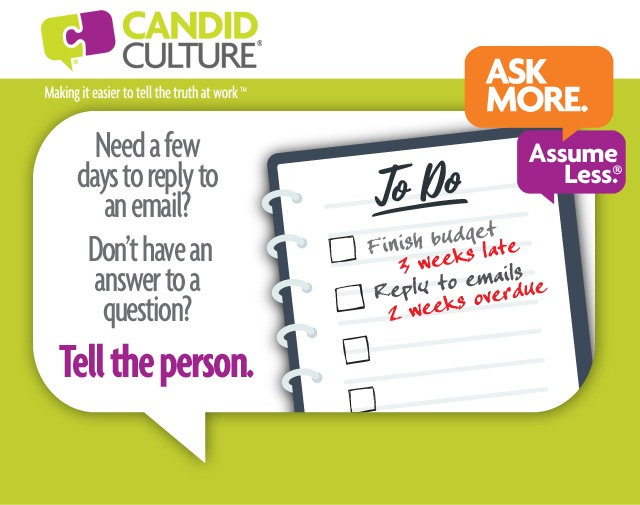

You open an email (or a few hundred) telling yourself you’ll reply later, but never do. Feeling ambitious, you agree to a deadline you can’t meet. Needing a break, you take a few days off but don’t put an out-of-office message on your email.

We’ve all taken too long to reply to an email, missed a deadline, or simply taken too long to provide someone with information. It’s ok to take time to respond, not to have all the answers, and take time off. We simply need to provide timely and accurate status updates.

When people don’t hear back from us in what they consider a timely way, they start to wonder (at best), and judge us (worse), or tell others we’re non-responsive and unreliable (worst). Don’t make people wonder if you received their message, send a timely status update and tell the truth.

If you’re behind and need more time than usual to respond to emails, tell people that. Respond to emails within 24-hours and tell senders you received their message and it will be (fill in the blank) before they hear back from you. When you get an email that requires research, respond within 24-hours and tell the person how long it will take to find the information. If you’re out of the office and don’t plan to read or respond to emails, tell people the dates you’re out.

In the absence of knowledge people make stuff up, and it’s never good. Filling in the blanks isn’t malicious. People simply have a need to know what’s happening. And when they don’t know, they invent stuff. It’s how the brain works. When we don’t hear back from people in what we consider a timely way, we start to wonder. “Did they get my message? Why aren’t they responding? What’s wrong?”

It’s ok to need time to respond. It’s ok to be running behind. It’s ok to take time off. Simply let people know the true status. Manage your reputation and business relationships. Don’t make people guess.

Last week one of my friends was concerned about something happening at her son’s school. She wrote out what she planned to say to the school principal and sent it to me to read. Her letter was long, with lots of unnecessary details. I read five paragraphs before understanding what the situation was even about. I revised her letter. My version was three sentences and easy to write. Why? Because it’s not my child and not my situation.

One of the things that makes giving feedback and making requests particularly difficult, is our emotional involvement. We’re invested in the outcome. The stakes feel high. And that emotion makes everything harder.

If you’re struggling with a message you need to deliver, get some help. The person who helps you craft a succinct, specific, and unemotional message doesn’t have to be a feedback expert or a manager. The person just can’t be involved. As long as the person isn’t emotionally involved, they’ll be helpful.

When you ask for help, don’t ask for advice. Instead of asking a friend or colleague, “What would you do in this situation,” ask, “What would you say?” These are very different questions. You want the specific words to resolve whatever you’re struggling with.

Asking someone for help planning a challenging conversation or message begs the question, isn’t asking for that type of help a form of gossip? It could be. So be careful who you ask.

When asking for help planning a message or conversation, ask someone in your organization who is at your same level or above (title-wise) or ask someone outside of the organization. Change the names of the people involved; protect people’s anonymity. And be clear if you are asking for help to plan a conversation or if you are venting. They are not the same.

The most effective feedback and requests are unemotional, factual, and succinct. Sometimes we need other people who are not involved to help us get there.

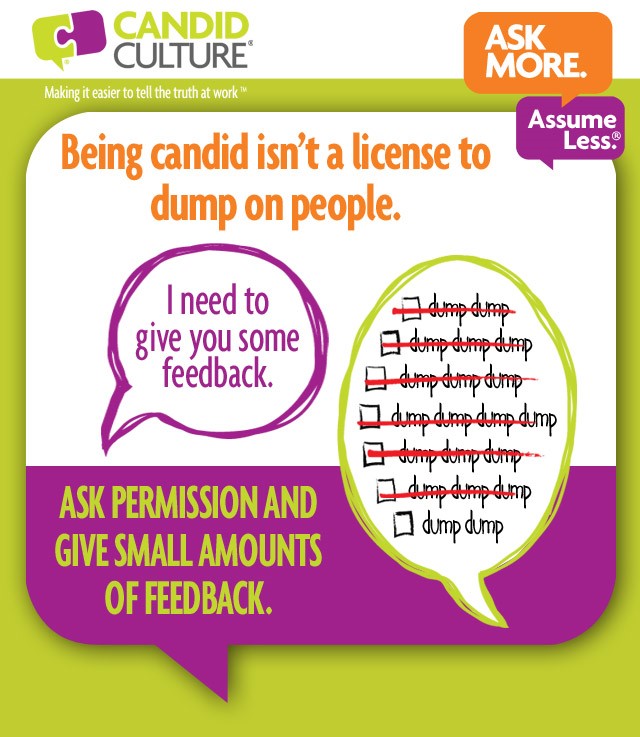

People leave feedback training armed with new skills and they unfortunately sometimes use those skills as a weapon. It goes something like this, “I need to have a candid conversation with you.” And then the person proceeds to dump, dump, dump. This couldn’t be more wrong, wrong, wrong.

When you give someone negative feedback you are essentially telling the person they did something wrong. And who likes to be wrong? The ego gets bruised, and people often start to question themselves. This normal reaction doesn’t mean you shouldn’t give feedback, you just need to do it judiciously.

Ask yourself these four questions when deciding whether or not to give someone feedback:

Let’s say you’re on the receiving end of too much feedback. What should you do? It’s ok to say “no thank you” to feedback. Here’s what you could say:

“Thank you for taking the time to bring this to my attention. I really appreciate it. You’ve given me a lot of feedback today. I’d like something to focus on that I can impact right now. What’s the most important thing I should do?” You’ve validated the other person and demonstrated openness and interest. You’ve also set some boundaries and expectations of what you will and won’t do.

“Thank you for taking the time to share your requests about… We won’t be making any changes to that and here’s why.” It’s ok not to act on all feedback, simply tell people why you won’t.

“I appreciate your concern. I’m not looking for feedback on that right now.” Can you say that to someone? Yes. Should you? Sometimes. To your boss – no. To someone who offers unsolicited advice that’s outside of their lane, yes. They’ll get the message.

People can only act on and digest small amounts of feedback at a time. Be judicious and assess your motives. The purpose of feedback is to be helpful, when the feedback is requested, and when you have the relationship to give it.

If you receive too much feedback or unsolicited feedback, it’s ok to decline. You’re not the 7-11, aka you’re not always open.

At the end of presentations, attendees often approach me and say something like, “People tell me my communication style is really direct and that it can be off putting. I don’t know what to do about this.” Or they say, “People say I’m really quiet and hard to read. They have a difficult time getting to know me.”

If you’ve been given the same feedback repeatedly, or know you create a first impression that may be challenging to others, set expectations and tell people about your communication style when you begin working with them. Don’t wait until they feel offended, confused, or frustrated. Simply tell people when you meet them, “I’ve been told that I’m too direct and how I provide feedback can be off putting. Anything I say is to be helpful. If I ever offend you or provide too much information, I hope you’ll tell me.” Or you could say something like, “I’m told that I’m quiet and it’s hard to get to know me. I’m more open than I may appear. If you want to know anything about me, feel free to ask.”

People will make decisions about and judge you. There is nothing you can do about this. But you can practice what I call, ‘get there first.’ Set people’s expectations about your communication style and what you’re like to work with, and then ask people to speak freely when they aren’t getting something they need.

The root of frustration and upset is violated expectations. People may not be aware of their expectations of you or be able to articulate those expectations, but if they didn’t have certain expectations, they wouldn’t be upset when you acted differently than how they (possibly unconsciously) expected.

I’m a proponent of anticipating challenges and talking about them before problems arise. If you know something about your behavior is off putting to others, why not be upfront about it.

When people interview to work for me, I set clear expectations about my communication style and what I’m like to work with. I tell them all the things I think they’ll like about working for me and all the things I suspect they won’t. I tell them the feedback I’ve received from past employees and things I’m working to alter. People often nod their heads and say, “no problem,” which, of course, may not be true. They won’t know how my style will impact them until they begin working with me. But when I do the things I warned them would likely be annoying, we can more easily talk about those behaviors, than if I had said nothing.

Talk about your communication style when projects and relationships begin. Replace judgment and damaged relationships with dialogue.

When you feel you’ve been wronged, it’s natural to want to lay into the offending person, give negative feedback, and tell him exactly what you think. The problem with doing this is that as soon as a person feels accused, he becomes defensive. And when people are put on the defensive and feel threatened, they stop listening. And you’ve potentially damaged your workplace relationship.

When someone does something for the first time that violates your expectations, use the lowest level of intervention necessary. Allow the person to save face, and ask for what you want, without giving an abundance of negative feedback and pointing out all the things he’s done wrong.

Likewise, when you cut your finger while cooking, you put a Band-Aid on your finger. You don’t cut off the finger. This is true with business communication too.

When you’re facilitating a meeting, you can ask the two people who are side talking to stop, or you can go third grade on them and ask, “Is there something you want to share with the rest of us?” Both methods will stop the behavior. But one embarrasses the side talkers a lot, the other only a little.

Likewise, when one of your coworkers takes credit for your work, you can give feedback and say, “I noticed you told Mike that you worked on that project, when we both know that you didn’t. Why did you do that?” Or you can skip the accusation and ask a question instead, saying, “I noticed you told Mike you worked on that project. Can I ask why you did that?” From there you can have a discussion, give feedback if you need to, and negotiate.

When your boss doesn’t make time to meet with you, rather than saying, “You don’t make time for me. That makes it hard for me to do my job and makes me feel unimportant.” Instead consider saying, “I know how busy you are. Your input is really important in helping me move forward with projects. How can we find 30 minutes a week to connect so I can get your input and stay on track?”

In each of the situations above, you’d be justified in calling the person out and giving negative feedback. And it might feel good in the moment. But being right doesn’t get you closer to what you want, and it can damage your workplace relationships.

Practice good business communication –say as little as you have to, to get what you want. If this method doesn’t work, then escalate, communicate more directly, and give direct feedback. The point is to get what you want, not to make the other person look bad. The better the ‘offender’ feels after the conversation, the more likely you are to get what you want in the future.

Get the words to say the hardest things in two minutes or less. If you work long enough, you’ll eventually be confronted with these situations. Giving feedback doesn’t have to be hard.

Last week one of my friends was concerned about something happening at her son’s school. She wrote out what she planned to say and sent it to me to read. Her notes were long, with lots of unnecessary details. I read five paragraphs before understanding what the situation was even about. I revised the notes. My notes were three sentences and easy to write. Why? Because it’s not my child, not my situation.

What makes giving feedback and making requests particularly difficult is our emotional involvement. We’re connected to the outcome. The stakes feel high. And that emotion makes everything harder.

If you’re struggling with a message you need to deliver, get some help. The person who helps you craft a succinct, specific, and unemotional message doesn’t have to be a feedback expert or a manager. The person just can’t be involved. As long as the person isn’t emotionally involved, they’ll be helpful.

When you ask for help, don’t ask for advice. Instead of asking a friend or colleague, “What would you do in this situation,” ask, “What would you say?” These are very different questions. You want the specific words to resolve whatever you’re struggling with.

Asking someone for help planning a challenging conversation or message begs the question, isn’t asking for that type of help a form of gossip? It could be. So be careful who you ask.

When asking for help planning a message or conversation, ask someone in your organization who is at your same level or above (title-wise) or ask someone outside of the organization. Change the names of the people involved; protect people’s anonymity. And be clear if you are asking for help to plan a conversation or if you are venting. They are not the same.

The most effective feedback and requests are unemotional, factual, and succinct. Sometimes we need other people who are not involved to help us get there.

It’s been almost two years that we’ve been looking into people’s homes on Zoom. Life and work have changed, and people have a variety of feelings about those changes. Some people miss working in person and can’t wait to go back to the office. Some people love working from home and never want to go back. What’s important is the ability to talk about how we feel and what we need from work – with the people we work for.

Most people suffer in silence, concerned to ask for what they want or need at work. Managers find out their employees are unhappy when they come across employees’ resumes on the internet.

The world has changed and how we interact needs to change to. Your manager may not be able to allow you to work from home all the time, but she certainly won’t if you don’t tell her what you want.

We need to cross the line, having conversations that perhaps we haven’t had in the past.

Managers, in addition to checking in on work progress, talk about how employees are doing and what they need going forward to be satisfied and do their best work.

Questions to ask during regular check-ins:

I’m not a fan of asking, “How are you doing?” It’s a vague question, and vague questions produce vague answers. But many employees will go their whole career without being asked how they’re doing. It demonstrates caring. It’s a place to start.

Here are some better questions to ask employees:

Managers, even if you ask these questions, employees may not feel comfortable answering. Managers can lead by example by talking about themselves. Share how your life, needs, and desires have changed. Share your own constraints. When managers show vulnerability, they convey it’s ok for employees to do so as well.

Also, tell employees that you really want to know the answers to the questions and assure employees there won’t be negative consequences for speaking candidly. Projects won’t be taken away. Careers won’t be impacted. You’re just talking. If employees never want to come into the office or travel, or want to work part-time, yes, jobs and careers may be impacted. But a conversation is just that, a conversation.

You won’t get what you don’t ask for.