Ask Better Questions and Stop Being Disappointed at Work

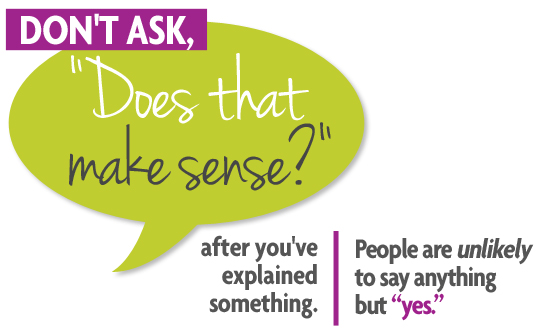

I’m taking golf lessons, which should frighten anyone within 100 feet. Every time the instructor explains something new, he asks me, “Does that make sense?” “Does that make sense” is a common clarifying question that many people ask, but it’s not a good question for two reasons.

Reason number one: If an explanation doesn’t make sense to me, I’m the idiot for not “getting it.” It’s not that the instructor hasn’t been clear, I just “didn’t get it.”

Reason number two: The question doesn’t force me to speak, thus the person asking the question doesn’t get any information. “Does that make sense” is like asking a shopper in a store, “Can I help you?” We all know the right answer to that question is, “No, I’m just looking.” This is a similar to when someone asks, “Are there any questions?” The right answer is “no.” And when people say “no,” the person who asked the question often says, “good,” affirming people for not asking questions and making it less likely that questions will be asked in the future.

The golf instructor should be asking me:

- What did you learn today?

- What are you planning to do as a result of what we’ve covered?

- What techniques did I demonstrate?

- Let me see how that form looks.

- What questions do you have for me?

If he asks me the clarifying questions above, he will know what I am likely to do on the golf course.

Here are some clarifying questions that will force people to talk and won’t make them feel stupid for asking questions. Instead of asking, “Does that make sense,” consider asking:

“I want to make sure I gave clear instructions. Will you tell me what I’m asking you to do?” You could also phrase the questions like this, “Just so I know how I landed, what do you think I’m asking/expecting you to do?”

** This may sound condescending and like micromanaging in writing, but the question can be asked in a supportive and non-judgmental manner.

I was talking with one of my clients a few months ago. She was very upset because she told one of her employees what to do and he didn’t do it. Frustrated, she said, “He knew what to do, and he didn’t do it.” I asked her, “How do you know that he knew what to do?” She replied, “I told him what to do and when I asked if he had any questions, he said no.”

Her situation is a common one. The right answer to “Do you have any questions” is “no.” And we’re surprised when we swing by the person’s desk two weeks later to get a status update on the project, and he hasn’t started working on it yet.

Here are some additional examples of clarifying and delegation questions. These questions will force people to speak, providing a clearer sense of what people know and are likely to do.

- What questions do you have?

- What are you planning to do first? If the person answers this question appropriately, ask what they are planning to do next. If they don’t answer the question appropriately, step in and give more direction.

Provided you trust that the person knows what to do, give a tight deadline and ask to review the person’s work in a few days. Give people some freedom, but not enough to waste a lot of time and go down a fruitless path. Delegation is something at which most managers can improve. More effective delegation will lead to fewer missed deadlines and frustrations in the workplace.